Introducing the Idea of Internal Monologue to Adolescents

Generally, by the time kids hit middle school, they’re familiar with the idea of an internal monologue. They’ve probably got a short list of examples to share about the voice they hear in their head when they’re struggling or they’ve just messed up. But it can sometimes be hard to truly understand just how pervasive that voice is, how quiet, how subtle, and how much it drives our decisions every day – especially if it doesn’t seem critical. The more we become aware of the stories our brains tell us, the easier it gets over time to challenge those stories and make more informed choices.

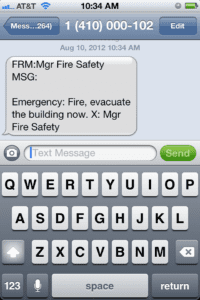

One powerful way to illustrate this is with something most middle and high school kids have in their back pocket all day – a smart phone. If they are like my kids, they have notifications that come in almost incessantly – who has liked their latest Instagram post or responded to their Snap or tried to FaceTime them. These notifications stimulate the emotion centers in our brains and are designed to compel us to action, and if the phone isn’t on silent, the ‘ping’ makes our heart rate go up when we hear it.

I experienced this yesterday when I set my phone across the room and started a 30-minute yoga practice. I was fully engrossed as I followed the instructor on video but then I heard my phone ping from the table about 20 feet away and I was able to watch as my mind set in to motion. Instantly, I was not paying attention to the video anymore, but wondering who was texting me. Was it my daughter who is away at college? Did she need something?

It pinged again. I wondered whether to check. Was it important? How would I feel if I interrupted my yoga practice to go check and it turned out to be SPAM? Would I have lost my momentum and give up on exercise for today?

It could also be my younger daughter. She was out for the day. What if she got in to a fender-bender or needed me to come get her?

Fortunately, I was able to divert my focus back to my yoga practice and reason that, if it were important, the next thing that would happen would be a phone call. I was amazed at how quickly my brain shifted gears and spun a story based on one little text tone and how, had I not been aware of what I was doing, I might have behaved very differently.

The consequences of either scenario were not huge, of course, but it is a terrific illustration of just how eager our brains are to respond to stimuli without many facts and conjure up a story that drives us to act immediately. If you’ve got teens in your home or your classroom consider setting up an exercise like this where you get them involved in some quiet activity such as reading or art or writing and have them keep their phone volume up. Ask them to notice what happens when they get a notification – how do they feel in their bodies, what is the narrative that starts in their brains.

Without judgment of any kind, it is interesting for us to know how our brains work – do they default to fear like mine did, instantly assuming that one of my kids was in danger or needed me, or do they anticipate that ping to be a notification that is positive? The more we pay attention to the tangents our minds lead us on, the more we can give ourselves space to choose how we respond to stimuli in our environment. In the end, that text message was a friend responding to a funny anecdote I’d sent the night before, so while it was welcome, it wasn’t urgent in the least, and I’m really glad I resisted the urge to stop my yoga practice to check it out.