How Social-Emotional Learning Helps Kids Become Healthy Adults

As parents and teachers, we are often uncomfortable when kids display strong emotions, with the exception of joy. For some reason, we generally love it when kids are joyful and happy. But when they are overwhelmingly angry or frustrated or sad, our first response is usually to tell them to tamp it down or talk them out of it.

“It’s not that bad.”

“Don’t cry.”

“Why are you getting so upset about something like that?”

Much of the time, especially with middle and high school aged girls, we dismiss their outbursts with an eye roll and label it drama. Boys are allowed to show anger or frustration and happiness, but almost never given an opportunity to cry. As the adults charged with helping these kids navigate the tricky waters of adolescence, these responses couldn’t be more harmful. Sending the message that there is only a small range of acceptable emotional responses to life events does not set them up to be healthy adults.

Healthy adults express a full range of emotions. Healthy adults have learned to accept their feelings and modulate their responses. Effective adults use their feelings to gauge their connection to something and often propel themselves forward into important work.

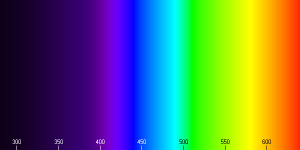

Unfortunately, emotions occur along a spectrum, like color. Purple bleeds into blue bleeds into green bleeds into yellow, etc. When you turn the light off, you can’t see any color at all. Our eyes (unless you’re color blind) are designed to see ranges of color; we can’t just block out everything but purple. In the same way, closing the door on what we consider to be “negative” emotions such as sadness or anger means that we are also shutting out happiness and excitement. It is impossible to selectively remove one or two feelings and still keep the capacity for others. Instead of sending our children the message that certain emotional responses are wrong or bad, it is important for us to teach them how to open the door to the entire range of human emotion. The more they realize that emotions are not to be feared or avoided, the better they will be able to handle them and use them to become more resilient.

It is often difficult for parents to watch their kids struggle with emotional pain and not be able to fix it. In the short run, it is much simpler to ask them to not share their pain with us, but we then risk losing the opportunity to be a safe haven for them to express sadness or fear. As school staff, it is often frustrating to hear about disagreements, especially when they are the same ones that happen year after year, but labeling them “drama” sends the message that only certain kinds of emotions are acceptable and it prevents us from seizing the learning moments that we are presented with.

Because middle and high school kids are so inundated with emotion, this is the perfect time to make a concerted effort to teach them to understand, identify, accept and positively act on those strong impulses. If we choose, instead, to look away or minimize, we won’t succeed in tamping down the feelings, but we will send the message that the feelings themselves or wrong or that we as adults cannot be trusted to share them with.