Tip for Parents and Educators (and Coaches and Mentors and …)

Human beings co-regulate our nervous systems with each other. We know that it is much easier to down-regulate our anxiety or fear or emotional pain with someone who is calm and welcoming than it is with someone who is feeling upset or nervous or in a hurry.

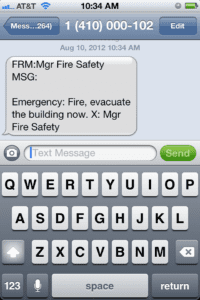

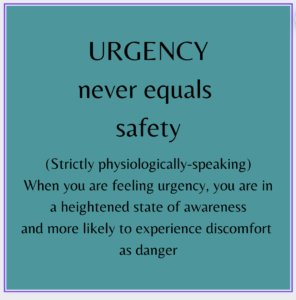

Because of the unique attributes of the adolescent brain, most of the information that is received by youth this age is processed through the emotional centers of the brain (the amygdala). This is also the center of fight/flight/freeze responses, so many adolescents walk around in some state of activation all day long. When they encounter an adult who speaks to them with urgency or gives off that urgency vibe (“Hurry up, sit down, everyone, we have a LOT to cover today!” or “Quick, get in the car! We only have 15 minutes to get to X before we’re late” or “I don’t have a lot of time, but if you can tell me what you need in the next five minutes, I can help you”), their nervous systems kick up a notch and that primes them for irritability, frustration, and even to start anticipating some sort of catastrophe or danger (or at least start looking for it).

Part of the problem with this is that when we are in fight/flight/freeze, the language processing portion of our brains goes offline. So if you’re feeling anxious to get this kid to hear you or follow directions or pay attention, you’ve actually just put them in to a state where they literally cannot do any of those things well. And they can also struggle to articulate what is going on for them because speaking clearly is hard when we’re in a heightened emotional state.

If you want to have smoother interactions with adolescents – either on the drive home from school or when you’re in the classroom or working with them 1:1 – take a minute to get out of urgency first. It’s not always possible; sometimes we are in a hurry, but even speaking that truth can help calm things down. “Sheesh, the traffic today was horrible and I’m feeling like I might miss the first 15 minutes of this really important meeting now.” As the adults who aren’t subject to the same emotionality as teens, it is incumbent upon us to get ourselves to a place of calm so that we can be present for the youth we are interacting with. The more we can down-regulate our own nervous systems, the more likely we are to be able to help kids do the same.