Tips for Parents: Conflict Resolution

I’m part of a task force that includes a number of different stakeholders with diverse backgrounds and opinions and desires and fears. We are doing important work and sometimes, it is amazing to me that we are able to move forward at all, given the complexity of the issue we’re trying to untangle and the range of ideas we bring to the table. And frankly, it wouldn’t happen if we didn’t have some amazing facilitators keeping us on track, pushing us out of our comfort zones, and sometimes using some pretty cool tools to help us get clarity.

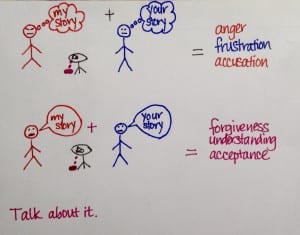

One such tool that I loved seemed to me to be immediately applicable to the parent/teen relationship, if only because it helps get us to the places where we really need to talk.

We were divided in to small groups of four to do this exercise, but I think it’s doable with one parent and one child, or as an entire family unit.

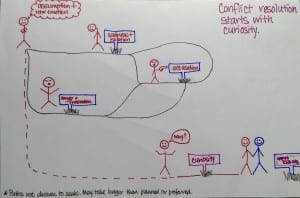

The first step is to identify what the issue is: for example, curfew or social media activity.

Next, talk about where your ideas Align and where they Diverge. Make a column for each and lists underneath. No explanation is necessary at this point, it’s just a way to identify where you all agree and where the ideas are different. It may seem simple, but it can be eye-opening to truly understand where everyone’s head is, and it might be surprising to realize that you align in quite a few areas (ie. kids’ safety, kids’ social connections, etc.)

It may be that the only thing anyone agrees on is that the current status is not workable for anyone, and that’s ok. It’s a starting point, and by defining what it is that everyone thinks is going awry with this current situation, you may discover some additional insights.

When you’ve made your lists, start exploring the divergence. Look for barriers and opportunities – is there a way to honor the alignment and build a solution? Even if you can’t come to consensus about the solution, this is a great way to learn something about each other and more fully flesh out where each individual’s values and priorities lie.