What are We So Afraid Of?

-

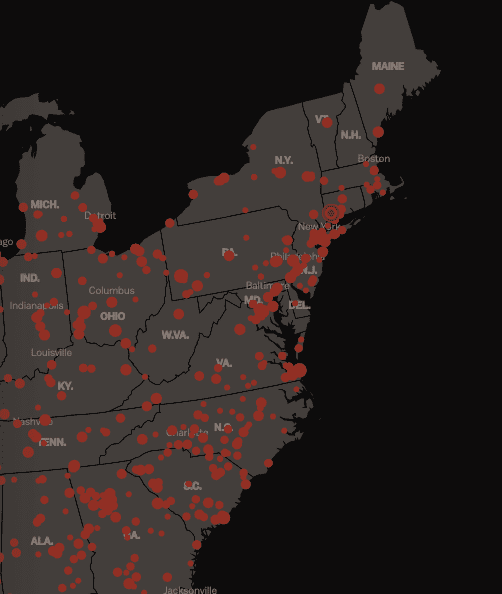

Mass Shootings Map from Vox.com

Following a(nother) spate of mass shootings across the United States, I am feeling frustrated, impotent, and incredibly sad. I don’t want us to collectively stay trapped in this loop of grief, anger, and paralysis, and I believe we are beginning to have the kinds of conversations we need to have, but I also feel an urgency about spurring those conversations on in a way that feels proactive and hopeful. I admit to weaving back and forth between signing petitions and donating to organizations fighting gun violence and amplifying tweets from people in power whose words I think are important to sitting quietly in despair and sadness.

I have long understood that anger is rooted in fear, and when I look around, I see so many people who are swimming in those waters. We are perpetuating generational fear in so many ways and it will take a deliberate, determined effort to break that cycle. We need to start having some difficult conversations with our kids and really listening to them. We need to change the way we relate to them and focus on making sure they feel loved and safe in relationship so that when they go out in to the world they aren’t hurting people.

I was a kid who swam in the waters of fear. My parents were both fearful people and they made a lot of their biggest decisions out of fear. I learned that the world was a scary place, that unconditional love was a fairy tale, and that nothing would get done unless I did it for myself. It’s a toxic way to live and it took a lot of therapy and a few really special, loving people to show me that it’s possible to make your way through the world with a belief that people are good and loving, that I am part of something bigger.

The rhetoric that dominates our public sphere is one of fear and scarcity. It tells us that there isn’t enough for all of us, there are threats out there so we must always be on guard, the world is a dangerous place. When people begin to believe that, they buy guns to carry on their bodies at all times “just in case.” They have a physical reaction to those who look different or speak a different language than they do. And often, they attack pre-emptively. Much of this attacking takes place online, since that is a safe place to begin – writing hateful things about other people, sending threats that they won’t likely follow through on, building a coalition of like-minded individuals to help defend them.

But more and more often, it spills out in to the public sphere and becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The violent anger of white supremacy is rooted in fear – fear that people of color are ‘taking over,’ fear that they will strike at some point, fear that there isn’t enough. And in some cases, like Eliot Rogers and others who kill women and transgendered people, it is the fear that they themselves aren’t enough – that they aren’t loved, that they won’t be cherished and cared for.

This culture of fear is toxic, and combating it starts at home and has to happen in our schools, as well. More than reading and writing and number-crunching, we need to teach our kids that they are loved, that they are safe, that there is enough. We do that by listening to them, by paying attention to the things that they are most afraid of and addressing those things. It is a significant shift to make, and one that requires effort and, often, a “fake it til you feel it” approach – especially if we were raised with fear, ourselves. But it is absolutely necessary if we are to interrupt the cycle of hatred and violence.

We must shift from punishment to discipline.

We must curb our strongest emotional responses so as not to lash out in anger.

We must let our kids see our full range of emotional responses, talk to them about when we feel fear, and help them understand that the things we are most afraid of will almost never come to pass. We have to give them context and let them talk to us about their fears without judging or teasing them.

The three young white men who are responsible for killing scores of innocent people in Gilroy, El Paso, and Dayton in the last week were, I am certain, driven by fear. Fear that they learned a long time ago, that was perpetuated and encouraged by our political rhetoric. We teach young white men that it is acceptable to express their fear as anger in a variety of ways, and unless we want to keep stoking our own fears of dating, going out in public, and speaking our truth, we have to change the way we raise our kids.

And until we do significantly change the way we raise our kids, and interrupt this culture of fear, we have no business selling guns. They are the single deadliest weapon in our country, able to take the lives of innocent people more quickly and efficiently than any other weapon available to the public, and we can’t afford to have them in the hands of people whose fear has metastasized to anger, especially those who have been taught that their anger is righteous and justified and socially acceptable.