What is Non-Violent Communication and Why Does it Matter?

Bhuston at English Wikipedia [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

So what is it?

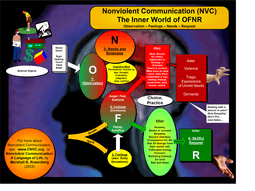

The term itself was coined by Marshall Rosenberg, a psychologist, whose life’s work revolved around the notion of compassionate connection and individual needs. He believed that if we could distill our communication with others down to which of our needs we were trying to get met, we could then begin to find strategies to meet those needs in concert with others rather than at odds with them.

Non-violent communication does not involve guilt or shame, power or control tactics, or manipulation. It is a way of communicating where each individual is sincerely interested in the needs of the other and validates their right to have those needs. It also involves taking personal responsibility for one’s feelings, actions, and sometimes, coming to terms with the fact that your needs cannot or won’t be met.

Why does it matter?

As teachers and parents, we generally assume a level of power and authority that can lead us to set up communication patterns with children that are rooted in violent communication (that is, shame/blame, power/control, manipulation). And while those tactics might work to keep things peaceful for a while, they aren’t long-term strategies for creating trusting relationships.

Threats of punishment, taking away privileges as a punishment, tit-for-tat rhetoric or behavior, and “because I said so” are all examples of this kind of violent communication. They might be effective at squashing behaviors short-term, but they won’t foster relationship or ultimately teach the child skills that will serve them as adults.

Non-violent communication is also about really understanding where someone else is coming from. Because it involves being really curious about what someone’s behaviors or rhetoric is trying to say about what needs they have that aren’t being met, it fosters compassion. I often use the phrases “hurt people hurt people” and “where there is bad behavior, there is pain.” Both of those are reflective of the notion that we express ourselves negatively when we need something we aren’t getting. Using non-violent communication techniques can help parents and teachers begin to understand what is at the root of certain behaviors or relationship dynamics.

We have all had at least one ‘a-ha’ moment when our assumptions about why a kid was acting out were proven to be horribly wrong. I once knew a mom whose (pre-verbal) toddler was throwing a massive tantrum and she got increasingly frustrated and angry as she tried nearly everything to calm him down – food, drink, cuddling, shushing, threatening. He was arching his back and pulling at his overalls and causing quite the scene. It was only when she finally laid him down to check his diaper that she realized he had somehow slipped a fork down inside his overalls and the tines were stabbing him in the genitals. No wonder he was screaming!

These techniques, when used by parents and teachers, are also a good way to teach kids how to get curious about their own feelings and motivations. So often, we react to pain or frustration in less than desirable ways without even really thinking about it, but the earlier we can learn to identify what is behind those strong feelings, the better. We will be able to express ourselves to people without them becoming defensive or angry and are more likely to get our needs met in the end. It’s an important life skill to have.

Think about how much easier your life might be if your co-worker or boss was able to come to you and say, “I am feeling really anxious right now because I need this report to be absolutely perfect. I know you’re on a deadline, but would you consider helping me by proofreading it?” That is non-violent communication. Unfortunately, there aren’t many adults who talk to others that way – especially when they’re stressed and anxious. What would it be like if more people did? The agitated person in line behind you, the police officer who is worried you pose a threat, your mother-in-law…. Don’t we want our kids to have this skill, too?

It also teaches us how to negotiate by helping find common ground. Because we all have needs, if both the adult and the adolescent can get really clear on what those needs are, they can also begin to work out whether the strategies each person has been using to meet those needs are at odds. If they are, there’s a chance to get creative and work together to find a solution that works for everyone.

The more we can find ways to work together to get all our needs met, the fewer stand-offs we’ll have. The fewer kids will get kicked out of class or their house.

Questions? Please comment below and I’ll do my best to answer them. If you want to know about NVC more in depth, check out any of the books by Marshall Rosenberg.